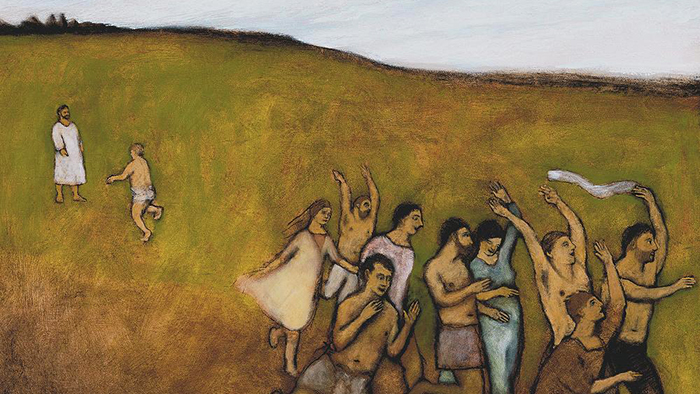

In scripture, God’s promise, revelation, and new truth are often brought not through what’s familiar or through those we know and who are like us but through a stranger. As Jews, Jesus and his disciples would have been immersed in the divisions within the Jewish and Samaritan cultures. The parable of the Good Samaritan and the Samaritan woman at the well demonstrates the existing cultural tension. Today, our reading from Luke’s gospel tells the story of the ten lepers and the only one to return to thank Jesus for his healing; he was the Samaritan. In these instances, the players in the story deal with individuals who are “strange” to them. In Parker Palmer’s work, The Company of Strangers, he writes: “The role of the stranger in our lives is vital in the context of the Christian faith, for the God of faith is one who continually speaks truth afresh, who continually makes all things new. God persistently challenges conventional truth and regularly upsets the world’s way of looking at things. It is no accident that this God is so often represented by the stranger, for the truth that God speaks in our lives is very strange indeed. Where the world sees impossibility, God sees potential. Where the world sees comfort, God sees idolatry. Where the world sees insecurity, God sees occasions for faith. Where the world sees death, God proclaims life. God uses the stranger to shake us from our conventional points of view, to remove the scales of worldly assumptions from our eyes.” Fr. Ron Rolheiser writes that the challenge Palmer presents concerns racism, sexism, provincialism, and sectarianism. Invariably, we are afraid of and un-welcoming to strangers – be they different vis-a-vis race, color, creed, gender, or sexual orientation. We fear what is different from ourselves. We are comfortable only with our own. However, within our own circles, much of the otherness of God cannot be revealed. Within familiar circles, good as these might be, there is too little in the way of promise, of newness. God can speak only a limited word here. Nothing is impossible with God, but that is only true when we move outside of our own circles. Like Jacob, we must wrestle in the dust with the stranger. In welcoming the stranger and showing genuine hospitality to those who seem foreign to us, whom we do not understand, we are given the opportunity to hear new promises and a fuller revelation of God.