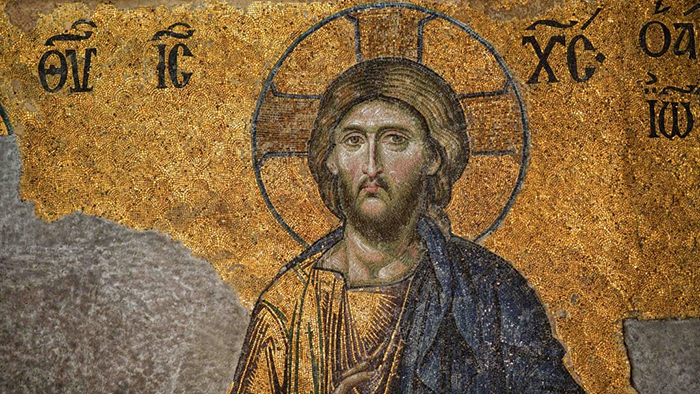

Scott Hahn, founder of the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology, writes that in the early Church, as today, Easter was the normal time for the baptism of adult converts. The sacrament was often called “illumination” or “enlightenment” because of the light that came with God’s saving grace. St. Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, speaks of the glory that leads to greater glories still: “May the eyes of your hearts be enlightened,” he writes, as he looks to the divinization of the believers. Fr. Ron Rolheiser writes that God put us into this world with huge hearts, hearts as deep as the Grand Canyon. As St. Augustine describes it, the human heart is not fulfilled by anything less than infinity itself. There’s nothing small about the human heart. The early Church Fathers taught that each of us has two hearts, two souls: there is a small, petty heart, a pusilla anima, which is the heart within which we are chronically irritated and angry, the heart within which we feel the unfairness of life, the heart within which we sense others as a threat, the heart within which we feel envy and bitterness, and the heart within which greed, lust, and selfishness breakthrough. But the Church Fathers taught that inside of each of us there was also another heart, a magna anima, a huge, deep, big, generous, and noble heart. This is the heart we operate out of when we are at our best. This is the heart within which we feel empathy and compassion. This is the heart within which we are enflamed with noble ideals. Inside each of us, sadly often buried under suffocating wounds that keep if far from the surface, lies the heart of a saint, bursting to get out. St. Paul’s words today to the Ephesians speak to their “hope” in “his inheritance among the holy ones,” the saints who have been adopted into God’s family and now rule with him. It’s the good news we must spread today within the hugeness of our hearts, where we inchoately feel God’s presence in faith and hope and proclaim to others in charity, forgiveness, and through our lived life that God has infinite love for every one of us.