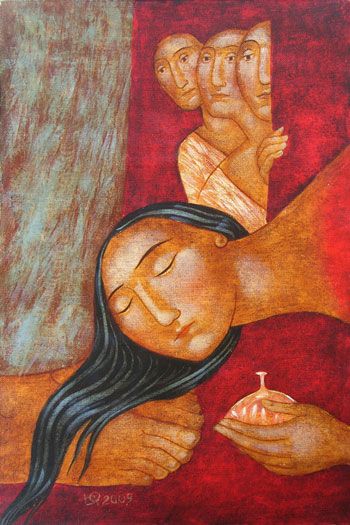

For Christians, the Easter holiday is about recapturing the surprise, excitement, and strangeness that the Resurrection brought to Jesus’ first followers. Bishop Robert Barron writes that he has always been drawn to the tombs of famous people. When I was a student many years ago in Washington, D.C., I loved visiting the Kennedy brothers’ graves on that lovely hillside in front of the Custis-Lee Mansion. In Paris, I frequently toured Père Lachaise Cemetery, the resting place of, among many others, Chopin, Oscar Wilde, Abelard, and Jim Morrison. When on retreat at St. Meinrad Monastery in southern Indiana, I would often take a morning to visit the nearby Lincoln Boyhood Memorial, on the grounds of which is the simple grave of Nancy Hanks, Abraham Lincoln’s mother, who died in 1818. I always found it profoundly moving to see the resting place of this backwoods woman, who died uncelebrated at the age of 35, covered in pennies adorned with the image of her famous son. Cemeteries are places to ponder, muse, give thanks, perhaps smile ruefully, and ultimately, places of rest and finality. The last thing one would realistically expect at a grave is novelty and surprise. Then, there is the tomb featured in the story of Easter. We are told in the Bible that three women, friends and followers of Jesus, came to the tomb of their Master early on the Sunday morning following his crucifixion to anoint his body. Undoubtedly, they anticipated that, while performing this task, they would wistfully recall what their friend had said and done. Perhaps they would express their frustration at those who had brought him to this point, betraying, denying, and running from him in his hour of need. Certainly, they expected to weep in their grief. But when they arrived, they found, to their surprise, that the heavy stone had been rolled away from the tomb’s entrance. Had a grave robber been at work? Their astonishment only intensified when they spied inside the grave, not the body of Jesus, but a young man clothed in white, blithely announcing, “You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him.” Unlike any of the other great religious founders, Jesus consistently spoke and acted in the very person of God. Declaring a man’s sins forgiven, referring to himself as greater than the Temple, claiming lordship over the Sabbath and authority over the Torah, insisting that his followers love him more than their mothers and fathers, more than their very lives, Jesus assumed a divine prerogative. And it was precisely this apparently blasphemous pretension that led so many of his contemporaries to oppose him. After his awful death on an instrument of torture, even his closest followers became convinced that he must have been delusional and misguided. The Resurrection of Jesus from the dead showed that this spiritual resistance was not in vain. When he appeared to his disciples, the New Testament tells us, the risen Lord typically did two things: He showed his wounds and spoke the word Shalom, peace. On the one hand, Christians should not forget the depth of human depravity, the sin that contributed to the death of the Son of God. We know that God’s love, his offer of Shalom, is greater than our possible sin. Christians understood this precisely because human beings killed God, and God returned in forgiving love. In achingly beautiful poetry, St. Paul expressed this amazing grace: “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”