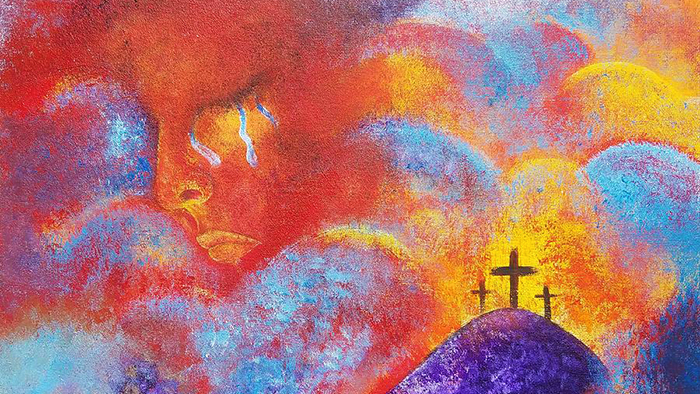

There was a Pharisee named Nicodemus, who was also a man of privilege and entitlement but disagreed with the Sadducees. As Pharisees, he and Jesus had much more in common, philosophically and religiously. In fact, there is reasonable scholarly speculation that Jesus was raised as a Pharisee. And so Jesus’ actions in the temple must have also caught Nicodemus’ attention because here, in the chapter that immediately follows the temple story, Nicodemus has come to Jesus in the night for fear of being seen by other members of the Sanhedrin. Rev. John Forman writes that Nicodemus recognized Jesus as a rabbi and asked him deep and probing questions. Without condemning Nicodemus’ understanding, Jesus invites him—and you and I—into a deeper embrace. Jesus, in our reflection verse, is testifying that those who trust and bond with the Beloved One will not perish, not because we have fulfilled a contractual obligation, but because we, too, have become God’s offspring, children of God. In that way, we receive from God the same family honor and character that God has, and we owe God the same loyalty that blood relatives give to each other. This is the way that God loved the world. God gave the world the only begotten child so that everyone who trusts and bonds with that child may not perish but have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the only begotten One into the world to judge creation but to save that creation through that One. Those who trust and bond with him are not judged, but those who hesitate and are disloyal to him are already judged because they have not trusted in the family name of the only begotten. God has loved us; God loves us and will love us. God loves us not because we have behaved correctly, because we have agreed to a checklist of doctrines, or even because we call ourselves Christians. God loves us because God is love. Loving is what God does, and God’s love abides. God’s love is wild and unconditional, not transactional. God simply delights in loving us because it is the essence of God’s being. And that is the essence that came to us in the Word made Flesh, Jesus Christ, the only Begotten child. Fr. Ronald Rolheiser, author of several of my favorite books on spirituality, has suggested that we are still a long way from trusting and bonding with the Word made Flesh and, in that way, taking on the family name. Fr. Rolheiser writes, “Do we ever really take the unconditional love of God seriously? Do we ever really take the joy of God seriously? Do we ever really believe that God loves us long before any sin we commit and long after every sin we commit? Do we ever really believe that God still, unconditionally, loves Satan and everyone in hell and that God is even now willing to open the gates of heaven to them? Do we ever really take how wide the embrace of God is? Do we ever believe Julian of Norwich when she tells us that God sits in the center of heaven, smiling, his face completely relaxed, looking like a marvelous symphony?” These are fantastic questions to be pondering during Lent, because as Rolheiser concludes, “the deep struggle of all religion is to enter into the joy of God.” As Jesus continues to offer light to Nicodemus there under the cover of night and to us here in the darkness of this Lenten season, Jesus also points to a sobering truth. Even if we have seen the light, we can still choose the darkness. We can choose not to be in relation to God. We can choose to fearfully imagine salvation to be a limited guarantee for the “there and then” and reject the life-sustaining intimate relationship that God deeply yearns for with us in the “here and now.” Choose life instead. Choose light. Choose love.