Since many will be searching for “all things Catholic,” we created a page that specifically addresses Catholic thought and traditions, as well as the role of Christianity in the development of Western Civilization.

Topics

The Big Bang was the brainchild of a Catholic priest

by James T. Keane

The Big Bang, which today is held as the beginning of the world, does not contradict the intervention of the divine creator, but requires it. Evolution in nature is not at odds with the notion of creation because evolution presupposes the creation of beings that evolve.

Who said it? Pope Francis, in 2014. If it surprises you that the leader of the world’s largest religious denomination would be such an unabashed fan of a materialist account of the creation of the world, you might be intrigued by two more data points. The Big Bang was the brainchild of a Catholic priest in 1927—and when Pope Pius XII seemed to endorse his theories…that priest told the pope to knock it off.

The Rev. Georges Lemaître was a Belgian priest but also a theoretical physicist and a mathematician. Born in 1894, he began studying for the priesthood in 1911 but joined the Belgian army in 1914, serving in World War I as an artillery officer. He was ordained for the Archdiocese of Mechelen-Brussels in 1923, also earning a doctorate along the way. While like many a priest-scholar before and since, Father Lemaître spent much of his life being mistaken for a Jesuit, he remained a diocesan priest and a member of the “Priestly Fraternity of the Friends of Jesus” throughout his life.

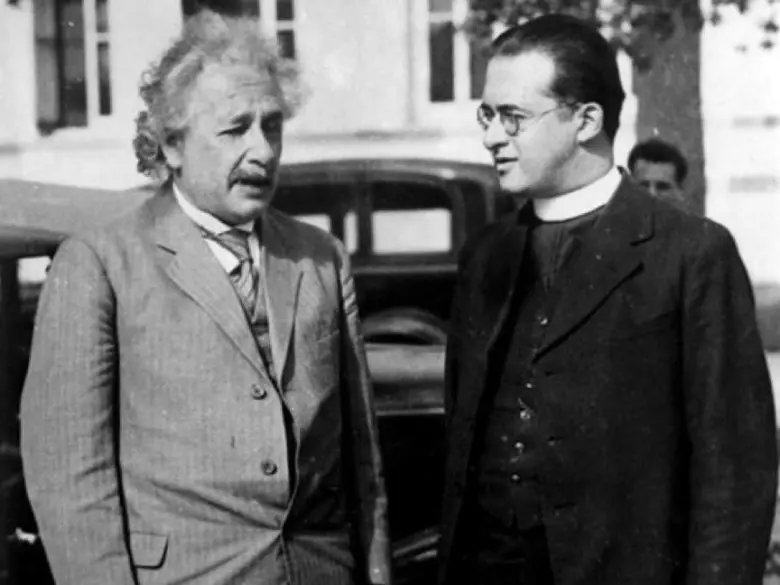

A professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain from 1927 until his retirement in 1964, Lemaître was awarded a second doctorate by M.I.T. in 1927. He was in constant conversation with other prominent physicists in those years, including Albert Einstein (with whom he is pictured above), whose equations describing the universe were an early research subject. Between 1927 and 1931, he formulated and then proposed his “hypothesis of the primeval atom,” what we know today as the Big Bang (originally meant as a sneer): the notion that the entire universe began from a single incredibly dense atom whose explosion billions of years ago, and ongoing disintegration, has formed all matter in the universe as well as the fabric of space-time.

Because most physicists up to then—including Einstein—believed the universe to be a static phenomenon, Lemaître’s idea was revolutionary, but eventually won acceptance by the larger academy. His work in the years that followed included an embrace of early computers to handle the increasingly complicated theoretical physics in which he and his peers were engaged.

Father Lemaître was surprised when Pope Pius XII weighed in on the Big Bang in a 1951 address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences at the Vatican (where Lemaître was present). “Indeed, it seems that the science of today, by going back in one leap millions of centuries, has succeeded in being a witness to that primordial Fiat Lux, when, out of nothing, there burst forth with matter a sea of light and radiation, while the particles of chemical elements split and reunited in millions of galaxies,” the pope said, adding further that science “has indicated their beginning in time at a period about five billion years ago, confirming with the concreteness of physical proofs the contingency of the universe and the well-founded deduction that about that time the cosmos issued from the hand of the Creator. Creation, therefore, in time, and therefore, a Creator; and consequently, God!”

Hold on a hot second, said Father Lemaître and others in the aftermath. On the one hand, the Catholic Church’s ongoing embrace of science should be seen as an almost unmitigated good; on the other, Lemaître thought the pope had gone too far in his comments, and told him so in the aftermath. Why?

We were blessed last week at America to have a visit from Guy Consolmagno, S.J., the outgoing director of the Vatican Observatory, and got a chance to ask him why Lemaître was upset with the pope’s words. Several reasons, he said, but first among them is that the Big Bang is a hypothesis, not a fact—and like most science, it will be revised and found to be incomplete (or false) at some point; it should not be equated with an eternal truth expressed poetically in Scripture. (This has of course already happened—Pope Pius XII’s “five billion years ago” now looks more like 14 billion years ago.)

Further, theology and science work best as dialogue partners in search of the truth; just as they need not be antagonists, they do not exist to justify the propositions of each other. Indeed, Lemaître had long argued that Catholic scientists should be careful to keep their faith separate from their science, once writing: “He does this not because his faith could involve him in difficulties, but because it has directly nothing in common with his scientific activity. After all, a Christian does not act differently from any non-believer as far as walking, or running, or swimming is concerned.”

“His conception of the relationship of science and faith was rather circumspect, carefully delineating their roles as ways of knowing,” Karl van Bibber, then professor and chairman of the Department of Nuclear Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, told America in 2016. “Science for him was the methodology for understanding the physical cosmos; revealed religion taught truths important for salvation. He was quite content to observe that the findings of science were in no way discordant with scriptural revelation, and vice versa, but neither should overreach.”

Pope Pius XII seems to have heeded Lemaître’s words—though that hasn’t stopped later popes, including St. John Paul II and the aforementioned Pope Francis—from giving credence if not a papal imprimatur to the Big Bang.

In 1959, Lemaître was appointed the second president of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He retired from Louvain in 1964.

Father Lemaître seems to have dodged another science/faith bullet during the 1960s, when Pope Paul VI asked him to serve on the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control. His failing health—and his suggestion that mathematicians shouldn’t weigh in on moral theology—led him to decline to participate in a process that eventually culminated with the encyclical “Humanae Vitae” in 1968.

Father Lemaître died in 1966 at the age of 71. Upon the 50th anniversary of his death in 2016, the Pontifical Academy of Sciences held a “Special Session on Cosmology” to recognize his achievements. The precis for the session noted that three days before Father Lemaître’s death, friends brought him news of the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation. If those waves are indeed the leftover radiation from the origin of the universe, it would go a long way toward bolstering the Big Bang hypothesis. “Je suis content,” Lemaître is said to have replied. “maintenant on a la preuve.”

“I’m happy. Now we have the proof.”

The saints aren’t flawless – and that should give us hope.

by Robert Ellsberg

My introduction to the saints dates back 50 years to my encounter with Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker, with whom I worked during the last years of her life. She herself has been proposed for canonization and is now officially on the first rung of this process, a declared Servant of God. Many suppose that she would have objected to this. After all, she is supposed to have said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.”

This remark represented more than the humility one might expect from any actual saint. She knew that most people regard saints as perfect people—close to God, but not entirely relatable to ordinary humans. As she once told me, “When they call you a saint it means that you are not to be taken seriously.”

Yet Dorothy Day took saints extremely seriously. Her speech was constantly populated by figures like St. Francis, St. Teresa of Ávila and her favorite, St. Thérèse of Lisieux. They were friends and companions, those who had found a way to live a Christ-centered life in their own time, and who challenged us to do the same.

There is something of the saint in all of us

Yet, if Dorothy didn’t want to be called a saint, she certainly wanted to be one. Right away, this reflected the distinction between the relatively small number of official saints—the tip of the iceberg, so to speak—and the vast numbers of “ordinary saints,” including those known only to God. A saint was not simply someone in a stained-glass window or the name of a church. The saint, she said, “is the holy man, the ‘whole man,’ the integrated man. We all wish to be that.” She believed we are all “called to be saints,” as St. Paul said, “and we might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name. We might also get used to recognizing the fact that there is some of the saint in all of us. Inasmuch as we are growing, putting off the old man and putting on Christ, there is some of the saint, the holy, the divine right there.”

If that is the case, we should look for inspiration not only to the canonized saints, the spiritual prodigies held up by the church for veneration. There are many all around us, perhaps not likely to pass through the canonical eye of a needle, in whom we could yet recognize “some of the saint…right there.”

Thus, among the stories of her favorite saints, Dorothy also appealed to a wider “cloud of witnesses,” including martyrs of the labor cause, peacemakers, prisoners of conscience, artists, philosophers and many who did not know Christ, yet would discover in the end that he was the hungry one, the homeless one or the stranger whom they fed, sheltered and welcomed. Of the Hindu Mohandas Gandhi, she went so far as to say: “There is no public figure who has more conformed his life to the life of Jesus Christ than Gandhi” or “carried about him more consistently the aura of divinized humanity.”

As for the official saints, she felt we must depict them “as they really were,” as human beings like ourselves, who struggled to find their way and remain on their path. To regard them only as legendary miracle workers actually dimmed our capacity to imagine that holiness had anything to do with us.

In introducing me to the world of the saints, Dorothy Day inspired a lifetime of thinking and writing about holiness and holy witnesses. What is more, she supported my inclination to look beyond the stories of “official” saints to reflect on many other spiritual guides, prophetic figures, and moral witnesses. Such stories help illuminate our path; they enlarge our hearts, and pose the question of what it might feel like to live such a life.

Unofficial saints

I have found further encouragement for this eclectic calendar in the teachings of Pope Francis. His speech before the U.S. Congress in 2015 was organized around “four great Americans,” including Dorothy Day, as well as Thomas Merton, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. This seemed to support the contention that we can derive inspiration and encouragement from a host of people who are not “official” saints, but who nevertheless help us “see and interpret reality in a new way.”

Pope Francis greatly elaborated on “the call to holiness in today’s world” in his apostolic exhortation “Gaudete et Exsultate”(“Rejoice and Be Glad”). In this document, he begins by renewing the teaching of the Second Vatican Council that all the faithful, “whatever their condition or state, are called by the Lord—each in his or her own way—to that perfect holiness by which the Father himself is perfect.”

In responding to this call, we are inspired by the great “cloud of witnesses” who surround us. These witnesses, he says, are not confined to the official saints but may include “our own mothers, grandmothers, or other loved ones….Their lives may not always have been perfect, yet even amid their faults and failings they kept moving forward and proved pleasing to the Lord.”

Pope Francis notes that many of the official saints are bishops, priests or religious, which may actually deter us from recognizing our own call to holiness:

We are frequently tempted to think that holiness is only for those who can withdraw from ordinary affairs to spend much time in prayer. That is not the case. We are all called to be holy by living our lives with love and by bearing witness in everything we do, wherever we find ourselves.

Saints aren’t perfect

Even in the case of official saints, we should not make the mistake of believing them to be flawless. Francis writes: “Not everything a saint says is completely faithful to the Gospel; not everything he or she does is authentic or perfect. What we need to contemplate is the totality of their life, their entire journey of growth in holiness, the reflection of Jesus Christ that emerges when we grasp their overall meaning as a person.”

Many of the official saints, especially those from earlier centuries, may appear strange or even off-putting in their rejection of “the world,” or their feats of extreme asceticism. Altogether, they reflect models of holiness that spoke to their own time and culture. As Pope Francis said, “Each saint is a mission, planted by [God], to reflect and embody, at a specific moment in history, a certain aspect of the Gospel.” Yet, still, they encourage us to think about the kinds of holiness that speak more directly to the needs of our time.

In any discussion of the official calendar of saints, it is impossible to avoid the preponderance, even in the modern era, of bishops, clergy and founders of religious orders. Given the resources and time it takes to move a cause from beginning to end, the advantage has always gone to religious communities and dioceses to initiate a cause and see it through to the end. But it is also true that the church has traditionally regarded those under religious vows, including celibacy, as the “saintly” class, as opposed to the great mass of “ordinary” faithful. Even today, it is exceptional for the church to recognize the forms of lay holiness, whether in family life, work or lay apostolates. The exceptions are generally martyrs and those who have borne suffering in a heroic manner.

Additionally, the traditional canon of saints is woefully imbalanced between men and women. This reflects the same impediments as above, as well as the fact that the process of canonization is entirely overseen by men.

Heroic discipleship

Nevertheless, I hope Catholics can recognize in many saintly stories figures whose holiness or witness was expressed not simply according to the all-too-stereotypical features of traditional hagiography, but in their wit, creativity and prophetic courage in circumventing obstacles; in claiming vocations and identities apart from those assigned by society or religious authorities; for doing what all saints do: demonstrating that a way of heroic discipleship is possible in all times, under all circumstances.

They share what Pope Francis called the true sign of the saints: they reject complacency; they go, like Jesus, to the margins and “fringes”; they exhibit boldness and passion. Above all, “they surprise us, they confound us, because by their lives they urge us to abandon a dull and dreary mediocrity.”

The Gospels do not speak of saints, but of disciples, apostles, people of faith and followers of Jesus. Jesus himself did not refer to saints but to those he called “Blessed”: the poor in spirit, the meek, the merciful, those who mourn, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the pure of heart, the peacemakers, those persecuted for righteousness’s sake. These are not exactly the typical criteria for canonization. But they describe the men and women—whether canonized or not—I have come to admire.

Christianity and Western Civilization

Christianity has had a profound influence on Western civilization for nearly two millennia. Its contributions shaped philosophy, law, culture, art, science, and social institutions. Here are some of the most noteworthy:

1. Human Dignity and the Value of the Person

- Rooted in the belief that every person is created in the image of God (imago Dei).

- Helped establish the foundation for human rights, equality, and the protection of the vulnerable (the poor, widows, orphans, and strangers).

- This Christian anthropology influenced modern concepts of individual worth and freedom.

2. Law, Justice, and Political Thought

- The natural law tradition, developed by thinkers like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, laid groundwork for Western legal systems.

- Concepts such as just war theory, rights of conscience, and moral limits on rulers grew out of Christian thought.

- The idea that rulers are subject to divine law contributed to constitutionalism and limited government.

3. Education and Scholarship

- The Church preserved classical learning after the fall of Rome.

- Medieval monasteries copied manuscripts and became centers of literacy.

- The first universities (Paris, Bologna, Oxford) grew out of cathedral schools and were Church-founded.

- The intellectual tradition of Christian theology encouraged inquiry, debate, and the integration of faith and reason.

4. Science and the Natural World

- Belief in a rational Creator who ordered the universe encouraged the assumption that nature is intelligible and consistent.

- Many pioneering scientists were devout Christians (e.g., Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Mendel).

- The Church funded astronomical research, hospitals for medical study, and botanical gardens for medicinal purposes.

5. Art, Music, and Literature

- Inspired some of the greatest works of architecture (cathedrals, basilicas), painting (Michelangelo, Raphael), music (Gregorian chant, Bach, Handel), and literature (Dante, Milton, Dostoevsky).

- Christian themes shaped Western artistic imagination, symbolism, and storytelling.

6. Morality and Ethics

- Christianity emphasized love of neighbor, forgiveness, humility, and care for the poor.

- These values reshaped cultural norms on charity, social responsibility, and the inherent worth of life.

- Opposition to practices like infanticide, slavery (over time), and gladiatorial combat arose from Christian moral convictions.

7. Social Institutions

- Hospitals: Christianity created the first institutional hospitals for the sick and poor.

- Charities: Orphanages, leper houses, and poor relief grew out of Christian concern for the marginalized.

- Marriage and family life: Elevated the dignity of women and children, emphasized mutual love in marriage, and promoted lifelong fidelity.

8. Cultural Identity and Unity

- Provided a unifying cultural framework for Europe in the Middle Ages, bridging kingdoms and languages.

- Shaped Western holidays, festivals, and the calendar (B.C./A.D., later BCE/CE).

- Christian symbols, rituals, and moral stories became embedded in Western cultural consciousness.

1. Symbols

- The Cross / Crucifix – The central symbol of Christianity, representing sacrifice, redemption, and hope.

- The Fish (Ichthys) – Early Christian secret sign, now a broad cultural shorthand for faith.

- The Dove – Symbol of the Holy Spirit and peace, widely used in politics and art.

- The Lamb – Innocence, sacrifice, and Christ as the “Lamb of God.”

- Bread and Wine – Eucharistic symbols, but also culturally tied to hospitality and covenant.

- Alpha and Omega (Α Ω) – God as beginning and end; seen in art, inscriptions, and literature.

- Light / Candle / Flame – Life, Christ as “Light of the World,” symbolic in ceremonies and art.

- Shepherd and Sheep – Care, guidance, and belonging; pastoral imagery in Western poetry.

2. Rituals

- Baptism – Cleansing, rebirth, and new beginnings; even secular culture uses “baptism by fire” metaphorically.

- Eucharist (Communion / Lord’s Supper) – Community, remembrance, thanksgiving; shaped cultural rituals of shared meals.

- Marriage Ceremony – Vows, rings, covenant—deeply influenced Western concepts of love and fidelity.

- Funeral Rites – Christian burial, prayers for the dead, and hope of resurrection influenced Western views of death and memorials.

- Lent and Easter – Ritual fasting, repentance, and spring renewal; Easter eggs and seasonal renewal imagery are cultural fixtures.

- Christmas – Nativity rituals blended with folk traditions; became a cornerstone of Western cultural celebrations.

- Confession / Forgiveness – Shaped ideas of accountability, honesty, and personal growth.

3. Moral Stories

- The Good Samaritan – Helping strangers and outsiders; universally invoked in law, healthcare, and humanitarianism.

- The Prodigal Son – Forgiveness, reconciliation, second chances; a recurring theme in literature and film.

- The Ten Commandments – Moral foundation for Western law and ethics.

- Creation and Fall (Adam & Eve) – Themes of temptation, innocence, and responsibility in countless works.

- Noah’s Ark – Survival, judgment, renewal; a powerful cultural metaphor for new beginnings.

- Moses and the Exodus – Freedom from oppression; deeply influential in liberation movements.

- David and Goliath – The underdog overcoming impossible odds; central to Western storytelling.

- The Passion and Resurrection of Christ – Sacrifice, suffering, and triumph over death; echoes in countless art forms and cultural archetypes.

- The Beatitudes and Sermon on the Mount – Ideals of mercy, humility, and peacemaking that shaped Western moral ideals.

9. Abolition and Social Reform

- Though Christians were complicit in slavery for centuries, Christian arguments eventually became central to abolition movements (e.g., William Wilberforce in England).

- Inspired movements for civil rights, workers’ rights, and humanitarian reforms.

10. Hope and Transcendence

- Christianity gave the West a vision of history as purposeful, not cyclical.

- It promoted belief in progress, redemption, and hope rooted in divine providence, influencing how Westerners understand time and destiny.

Contributions of the Catholic Church

The only Christian church in existence for the first 1,000 years of Christian history was the Roman Catholic Church (which we now simply call the Catholic Church). All other Christian churches that exist today can trace their lineage back to the Catholic Church. Most non-Catholic churches which exist today are less than a century or two old by comparison.

About 15 percent of all hospitals in the United States are Catholic hospitals. In some parts of the world, the Catholic Church provides the only healthcare, education and social services available to people.

Johannes Gutenberg, the inventor of the printing press, was Catholic and the first book ever printed was the Catholic Bible.

The Catholic Church is entirely responsible for the composition of the Bible, which books are included, as well as the breakup of the chapters and verses. Protestants have removed some books of the Bible because some of the verses were inconsistent with their theology (Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach and Baruch). Older, pre-Protestant Reformation Catholic translations of the Bible include them.

Why U.S. Catholics kneel during the Eucharist—and the rest of the world stands

(RNS) — In the United States, Catholics kneel during the Eucharistic prayer, while Catholics in the rest of the world stand. Many European churches, especially the older ones, do not even have kneelers.

Following the Second Vatican Council, the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM #43) mandated standing during the Eucharistic Prayer; however, the U.S. bishops requested an exception. In the United States, we kneel “except when prevented on occasion by reasons of health, lack of space, the large number of people present, or some other good reason.”

The bishops believed that American Catholics would be scandalized if they were asked to stand during the Eucharistic prayer. The Vatican granted the U.S. an exception to the universal rule.

While most people see standing as an innovation coming from Vatican II, in fact, kneelers became common in Catholic churches only in the last 200 years. Standing was the traditional practice. Eastern Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians always stood during the Eucharist.

In 325, the Council of Nicaea forbade kneeling on the Lord’s Day and in the days of Pentecost. The 1,700th anniversary of the council provides the American church with an opportunity to reexamine our practice of kneeling during the Eucharist, which is out of step with the rest of the church.

In canon 20, the council noted that “there are certain persons who kneel on the Lord’s Day and in the days of Pentecost,” but “it seems good to the Holy Synod that prayer be made to God standing.”

The Lord’s Day is, of course, Sunday, the day of the resurrection. The “days of Pentecost” refers to what today we call the Easter season, the days between Easter and Pentecost.

The Eucharist, the most important prayer of the church on the Lord’s Day, would be covered by this canon. The council did not refer to weekday Masses because they were not common at that time.

Standing while praying was the common practice in ancient times. Jews prayed standing in the temple and in synagogues. Pagans also prayed standing. One stands when worshipping God, when thanking God or when petitioning God.

Standing was seen as a mark of respect and honor. Today, even in non-religious situations, we stand as a sign of respect for judges and other officials.

Kneeling was seen as a sign of penance rather than respect. In the third century, Tertullian wrote, “We count fasting or kneeling in worship on the Lord’s Day to be unlawful.”

The Eucharist is not an act of penance; therefore, one should stand. It might be appropriate to kneel during Lent, but not on Sunday or during the Easter season when Christians joyfully celebrate the resurrection.

For early Christians, standing was a sign of freedom and Easter joy, because we stand with the risen Lord.

Irenæus, the second-century martyr and bishop of Lyons, explicitly equates not kneeling on Sundays and Pentecost as a symbol of the resurrection. In the fourth century, St. Basil said that when we stand on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, “we remind ourselves of the grace given to us by standing at prayer, not only because we rose with Christ, and are bound to ‘seek those things which are above,’ but because the day seems to us to be in some sense an image of the age which we expect.”

Kneeling as a sign of respect or devotion only came later. Catholics began kneeling at Mass in the 12th century at the time that the elevation of the consecrated host was introduced.

By this time, the common people did not understand the Latin prayers, and Communion had become less common. The Eucharist became more like Benediction, a time to adore Jesus in the sacrament. During Benediction, worshippers kneel.

Today, GIRM calls for Catholics to stand during the Eucharist except during the institutional narrative (aka consecration), when they are to kneel. If they do not kneel, they should bow when the priest genuflects after each consecration. Kneeling or bowing during the consecration is a compromise. It shows respect to Jesus in the Eucharist but still maintains the ancient practice of standing when praying to God. The Eucharist, after all, is a prayer with Jesus to the Father, not a prayer to Jesus.

The GIRM, first published in 1969 and revised in 2002, calls on the congregation to take the same postures during Mass as a “sign of unity.” We should all stand, kneel and sit in unison. GIRM states that postures should not be based on “private inclination or arbitrary choice.”

The Eucharist is a community experience, not a private devotion where you can do what you want. This might also apply to those who insist on kneeling when receiving Communion. While one may feel called to kneel out of piety, one’s personal preferences must be restrained in a common liturgical celebration, otherwise the “sign of unity” is fractured.

The 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea is an appropriate time for the U.S. church to reconsider its deviation from the general practice of standing during the Eucharistic prayer.

Each diocesan bishop could do this on his own if he wants, since even in the United States, standing is allowed for a “good reason.” Good reasons would include the desire to be in unity with the universal church or the desire of his people to stand. [Thomas J. Reese]

Making Sense of Relics and Pilgrimages

Some things about the Catholic Faith rouse the hearts and passions of the faithful, but appear strange, even absurd, to those on the outside. Catholic devotion to relics may well be at the top of that list.

Underlying Catholic esteem for relics is the reality of the Incarnation: God became man in space and time, thereby sanctifying the material order. Not only is the material creation “good” (see Genesis 1), God uses the material order to sanctify us, especially through the sacraments.

This is a matter of God coming down to us—to meet us where we are, in our flesh and all our physicality. In other words, God doesn’t need the sacraments; they are gifts to us, to sanctify us in a manner commensurate with our physical nature. We don’t honor God if we disregard with indifference the gifts he has so graciously given us.

When God performs miracles through the mediation of a saint’s relics, it’s the same thing—a gift to us, through the power of the saint’s intercession, through the medium of his or her earthly remains. The relic as such doesn’t perform the miracle; it’s always God working through the relic (and God working through the saint’s prayers). God chooses on occasion to act this way in order to help us grow in our faith, giving us a physical sign of his constant spiritual work, not to mention a physical sign of the true reality of the communion of saints.

Biblical Basis of Relics

Further, relics actually have a basis in the Bible. In the Old Testament, a brief story is recounted of a man who died and while he was being buried, a marauding band came by; the man was quickly thrown into the prophet Elisha’s grave which was nearby. The Bible tells us that “as soon as the man touched the bones of Elisha, he revived and stood on his feet” (2 Kings 13:21). Here, God worked a miracle through contact with Elisha’s earthly remains, his relics. Of course, God could have done this without the relic. But doing so through the mediation of the relic gives us a tangible sign of the power of the saint’s ongoing presence.

Two other examples stand out in the New Testament. In Acts of the Apostles, healings are said to have occurred through contact with Peter’s shadow: “Now many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the apostles … so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds and pallets, that as Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on some of them” (Acts 5:12-15).

Later, with Paul, a similar incident occurs: “And God did extraordinary miracles by the hands of Paul, so that handkerchiefs or aprons were carried away from his body to the sick, and diseases left them and the evil spirits came out of them” (Acts 19:11-12).

The early Church eagerly gathered the remains of her saints, especially the martyrs. This was not a matter of superstition, but a conviction that God works through the material order. And he often graces his Church with physical signs of his abiding spiritual presence, as well as physical signs of the ongoing vitality of his saints and their continued love for us.

Christianity is not merely an idea. Rather, Christianity is about God’s search for us, a search that occurs in history, in real space and time. This gives Christianity a gritty, historical, and concrete quality that is very different from mere myth or a vague spirituality.

One can readily see this difference by noting Christianity’s intensely missionary character. From the outset, Christians traveled the known world because they encountered a person; they listened to, touched, and supped with the God-man Jesus Christ and they knew it (see Luke 24: 36-43). They didn’t become missionaries because they encountered an interesting new idea—that wouldn’t have transformed the Roman world.

Pilgrimage

Biblical faith has also always been a pilgrimage faith. For example, in the Old Testament, males were required to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the feasts of Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles (see Exodus 34:22-23). This is what brought Mary and Joseph and the twelve-year-old Jesus to Jerusalem during the Passover (Luke 2:41-51). These feasts commemorated God’s great acts of salvation, acts which occurred in history

Christians quickly followed suit, showing an earnest desire to be where Jesus was, to walk where he walked—or to travel where God’s mighty work had been manifest in a particular saint.

Pilgrimage, relics, and the sacraments all stem from the logic of the Incarnation. God became one of us, to touch us and allow us to touch him; He came down to meet us where we are, in order to raise us up to where he is. This is the wondrous mystery of Christianity—the great exchange, whereby he takes on our humanity, in order to elevate us to share in his divinity. [Dr. Andrew Swafford – Ascension Press]