Sam Keen holds both a master’s degree in divinity and a doctorate in the philosophy of religion. He calls himself a “trustful agnostic,” a “recovering Presbyterian” and wears a question mark rather than a cross around his neck. He sees himself as a searcher on a spiritual quest. He writes that in the spiritual quest you never, in this life, really arrive. For him, once a person settles into the practice of a religion, he or she can no longer claim to be on a spiritual quest. Spirituality has been traded in for religion.

In saying this, Keen speaks for our age. Spirituality is in, religion is out. Typical today is the person who wants faith but not the church, the questions but not the answers, the religious but not the ecclesial, truth but not obedience.

The churches are dying right in the middle of a spiritual renaissance. More and more typical too is the person who understands himself or herself as a “recovering Christian,” as someone whose quest for God has taken them out of the church. Why are so many people who are sincerely searching for God not turning to the churches? Why is there so much disillusionment with organized religion?

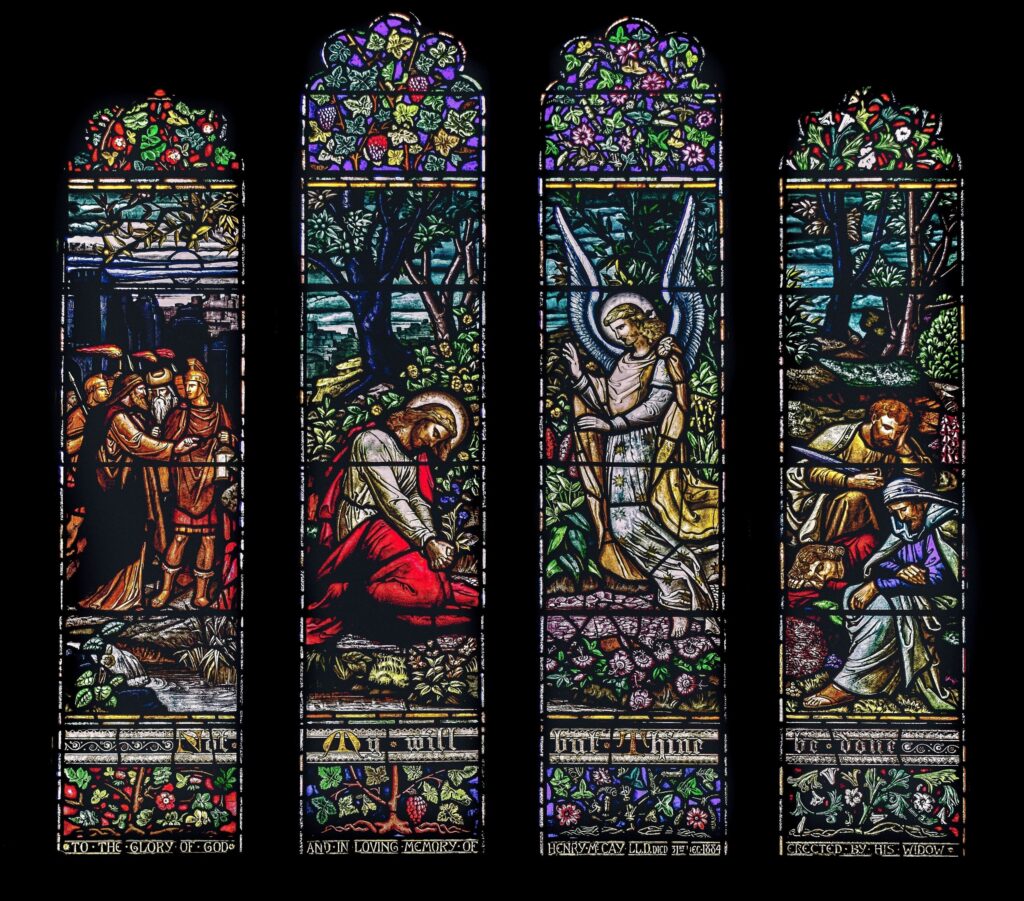

It is futile to argue that the world should perceive us, the churches, more kindly. You can’t argue with a perception! Better to admit our shortcomings. We are, right now, far from being the community we should be: We are intellectually slovenly, we don’t live adequately enough what we preach, we close off questions prematurely, and we radiate too little of the charity, forgiveness and joy of God.

Bluntly put, I don’t see a lot of people with question marks around their necks being crucified. There is too much glamor and too little commitment in it. Moreover there is also some intellectual dishonesty in it. The pure quest that does not want a hard answer is ultimately trying to avoid something, actual commitment. As C.S. Lewis puts it: “Thirst is made for water; inquiry for truth.” Sometimes what we “call the free play of inquiry has neither more or less to do with the ends for which intelligence was given than masturbation has to do with marriage.” The spiritual quest is about questions—and it is also about answers. [Excerpt from Ron Rolheiser’s “Questions Without Answers” September 1994]