Who is my neighbor? What does it mean to be neighbor to one another? Jesus once answered this by telling us the parable of the Good Samaritan. One of the interesting things in this parable is that those who did not stop to help him, the priest and the scribe, did so for reasons that go far beyond the question of their individual selfishness and selflessness. They did so for certain ideological, religious reasons. One of the interesting things in this parable is that those who did not stop to help him, the priest and the scribe, did so for reasons that go far beyond the question of their individual selfishness and selflessness. They did so for certain ideological, religious reasons. Thus, the priest did not stop because he feared that the man was dead and, being a priest, if he touched a dead body he would be ritually defiled and thereby unable to offer sacrifice in the temple. The scribe had his own religious reasons for not stopping. The Samaritan, who had the least to lose religiously, was able to be moved by simple human compassion. What if we updated the characters in the story to modern day roles – how would that change our choices?

One day a man was taking a walk in a city park when he was mugged, beaten up, and left for dead by a gang of thugs. It so happened that, as he lay there, the provincial superior of a major religious order walked by and saw him. He thought to himself: “If I help this man, I will set a dangerous precedent. Then what will I do? Having helped him, where will I draw the line? This is ultimately a question of fairness.” And thus he passed him by.

A short time later, a young woman, a theology student, happened to come along. She too saw the man lying wounded. Her first instinct was to stop and help him, but a number of thoughts made her hesitate. “The course on pastoral care I just took, taught that it is not good to try to rescue someone. It’s simply a savior complex which doesn’t do the other person any good in the long run and comes out of a less than pure motivation besides. I would only be trying to help that person because it makes me feel good and useful. It would be a selfish act really; ultimately only this man can help himself.” So, she too, passed by the wounded person.

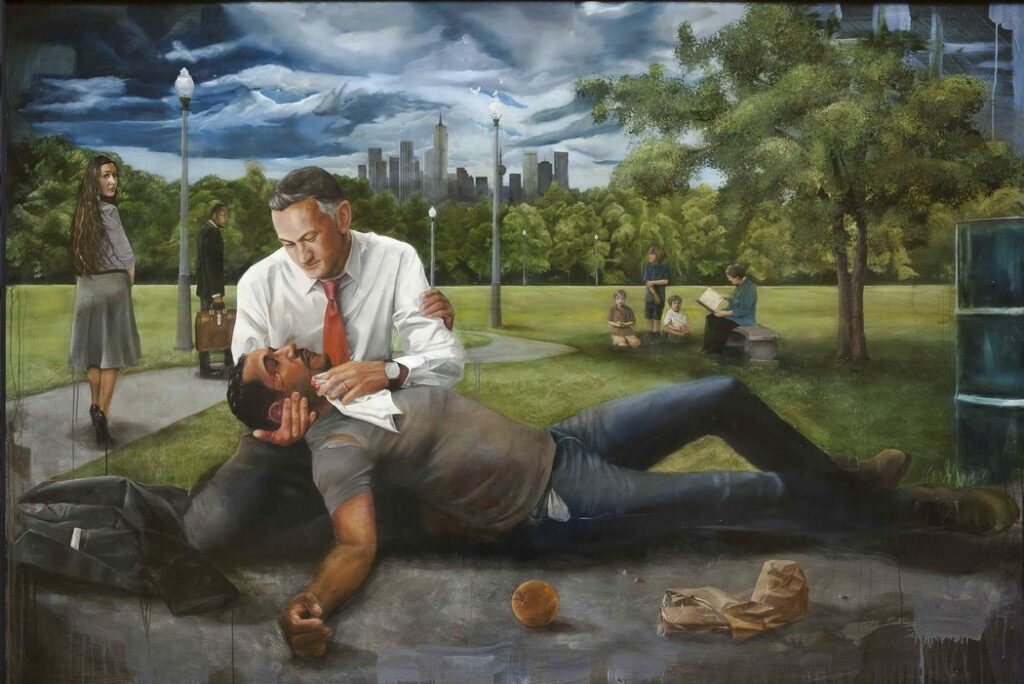

Finally, the CEO of Texaco Oil happened to be out joy riding in the new BMW he had just purchased. He chanced to see the wounded man lying there. Seeing the face of that wounded person, something in him suddenly changed. A compassion he didn’t even know he possessed took possession of him. Tears filled his eyes and, deeply moved, he got out of his car, bent over, and gently picked up the man. He carried him to his car and gently laid him in the back seat, oblivious of the fact that blood was staining the clean white upholstery. Arriving at the emergency entrance of the nearest hospital, he rushed in and hollered for the paramedics. After a stretcher had brought the man into the emergency room, they discovered that he had no medical insurance. The CEO produced a Visa Gold Card and told the hospital staff to give the wounded man the best medical attention possible money was to be no object. He promised to cover all hospital expenses.

Who was neighbor to the wounded man? [Adaptation of Ron Rolheiser’s “The Good Samaritan” July 2016]