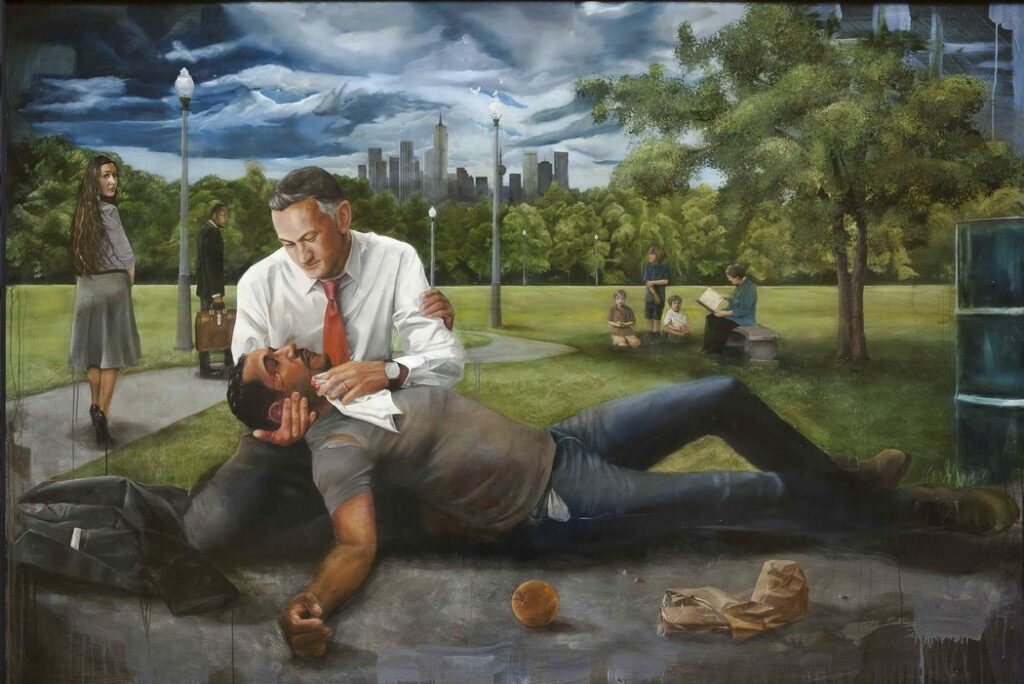

What would Jesus do? For some Christians, that’s the easy answer to every question. In every situation all we need to ask is: What would Jesus do? At a deep level, that’s actually true. Jesus is the ultimate criterion. He is the way, the truth, and the life and anything that contradicts him is not a way to God. But Jesus’ life presented complexities. We see that sometimes he did things one way, sometimes another way, and sometimes he started out doing something one way and ended up changing his mind and doing it in a different way, as we see in his interaction with the Syro-Phoenician woman.

That’s why, I suspect, within Christianity there are so many different denominations, spiritualities, and ways of worship, each with its own interpretation of Jesus. Jesus is complex. So where does this leave us?

Well, the way of most Christian denominations, is where we submit our private interpretation to the canonical (“dogmatic”) tradition of our particular church and accept, though not in blind, uncritical, obedience, the interpretation of that larger community, its longer history, and its wider experience, humbly accepting that it can be naïve (and arrogant) to bracket 2000 years of Christian experience so as to believe that our insight into Jesus is a needed corrective to a vision that has inspired so many millions of people through so many centuries.

Still, we’re not meant to park the dictates of our private conscience, our critical questions, our unease with certain things, and the wounds we carry, at our church door either. What would Jesus do? We need to answer that for ourselves by faithfully holding and carrying within us the tension between being obedient to our churches and not betraying the critical voices within our own conscience. If we do that honestly, one thing will eventually constellate inside us as an absolute: God is good! Everything Jesus taught and incarnated was predicated on that truth. Anything that jeopardizes or belies that, be it a church, a theology, a liturgical practice, or a spirituality is wrong.

What would Jesus do? Admittedly the question is complex. However we know we have the wrong answer whenever we make God anything less than fully good, whenever we set conditions for unconditional love, and whenever, however subtly, we block access to God and God’s mercy. [Excerpt from Ron Rolheiser’s “Anchoring Ourselves Within God’s Goodness” December 2019]